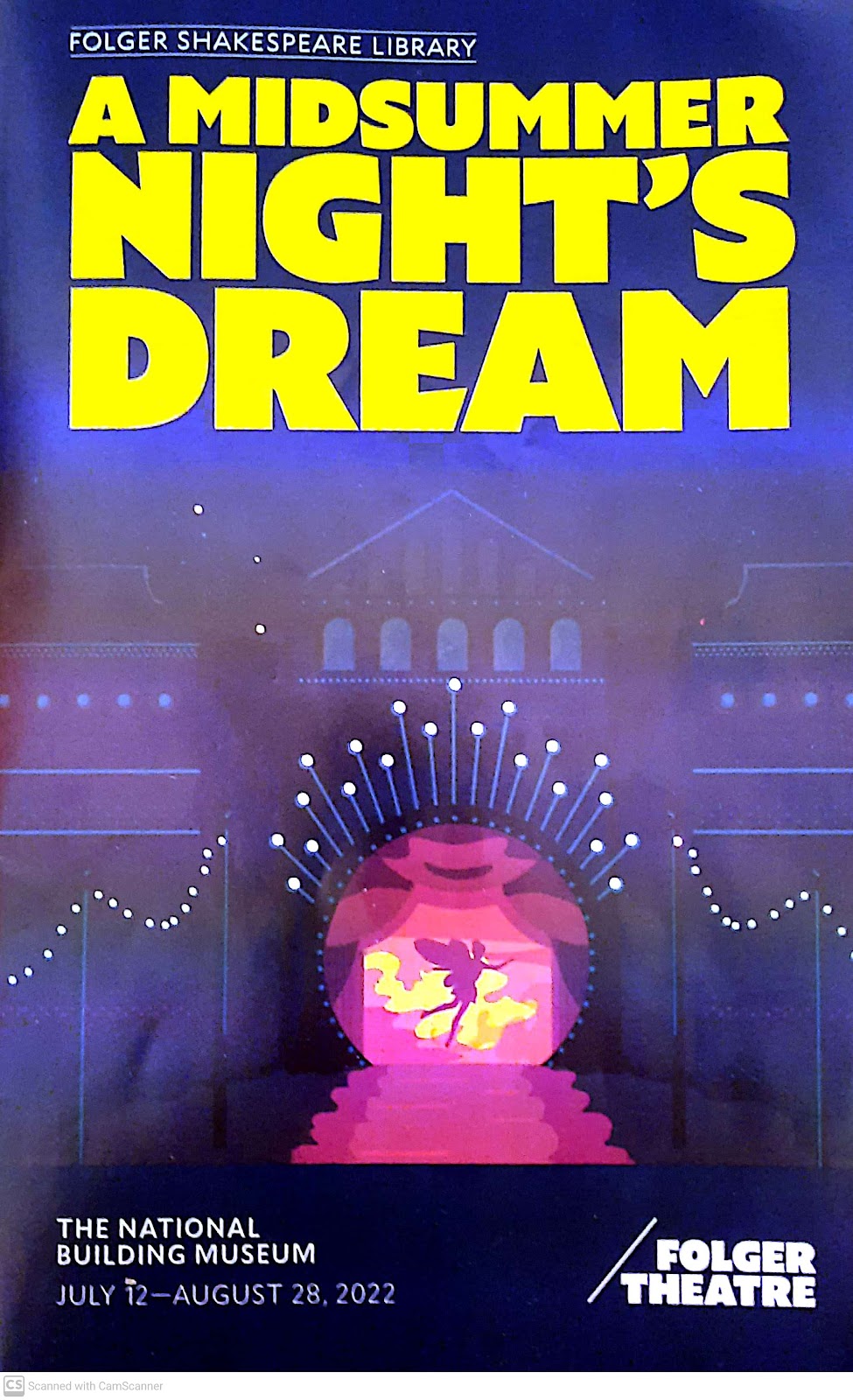

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Folger Theatre, Washington, DC

Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream is many

things: a comedy, a romance, a fantasy, even a revenge drama. The most often

produced of Shakespeare’s plays, it has always been a fan favorite. I had my

own experiences with it, once upon a time, many, many years ago, when I acted

in a college production of it – as Peter Quince, the carpenter who directs “the

play within the play.”

I have never been a Shakespeare purist. I celebrate

colorblind casting and have seen well-executed performances by women playing

male characters. (Remember, all of Shakespeare’s plays were originally staged

with men playing all of the roles.) I’ve seen successful productions that were

set in different time periods. I remember a touring production of Much Ado

About Nothing set in 1950s Cuba that I saw in Durham, NC, over 30 years

ago.

But this “adaptation” of Shakespeare’s play, produced by the

Washington’s Folger Theatre at the National Building Museum this summer, was

“impure” enough to bring out a bit of the purist in me. As adapted and directed by Victor Malana Maog, this 90-minute Midsummer goes too far – rearranging

scenes (the play starts with Act I, Scene 2, followed by Act I, Scene 1),

switching characters’ genders (Titania puts her spell on Oberon rather than

vice versa), interpolating contemporary expressions and including references

based on the race of the actor (at least twice, the African American actor

playing Bottom mentions “Black baby Jesus”), and using modern music (an

instrumental version of “Dream a Little Dream of Me” plays at the beginning of

the play and several times afterward). I don’t know the play well enough to

determine what scenes may have been compressed or cut, but to get the running

time down to 90 minutes, there must have been some editing.

Recently there has been coverage of an unauthorized

production of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton by a church in Texas, in

which specific conservative religious content was inserted, antithetical to the

messaging of the iconic musical. Miranda, appropriately, sued to stop the

production. I was reminded of that during this Midsummer. Were he alive

today, I would encourage Shakespeare to file a similar suit.

For those who may be unfamiliar with the play, a conflict

between the king and queen of the fairies coincides with preparations for a

royal wedding. A group of tradesmen prepare a play to be presented as part of

the wedding celebration. Caught up in this madness is a pair of young couples involved

in a romantic triangle. The fairies distribute magical potions to give one of

the tradesmen the head of an ass and causes the fairy king (this is where the

characters are changed) to fall in love with the ass when he awakens from his

sleep. Similarly, misdirecting the potion on the young lovers changes their

dynamic, confusing matters even more. Everything comes to a happy ending as the

fairy king and queen reunite and the royal wedding takes place, followed by the

tradesmen’s performance.

The design team included Tony Cisek (production), Jim Hunter

(festival stage), Olivera Gajic (costumes), Yael Lubetzky (lighting), and

Brandon Wolcott (sound and composer). The production was visually striking,

making excellent use of the “playhouse” (festival stage) constructed within the

cavernous space of the National Building Museum. The costumes are a combination

of contemporary and fantasy, sometimes overpowering the action. Because this

was an afternoon matinee in a space filled with natural light, lighting effects

had minimal impact. The sound was tricky to balance in the unusual space.

The acting ranged from the bloviating of Jacob Ming-Trent as

Bottom to the fire of Renea S. Brown as Helena, with more falling toward the

overacting side of the continuum. Danaya Esperanza’s Puck demonstrated a mischievous

and mysterious air, even when bouncing about a purple balloon at the beginning

and ending of the performance. Since I once played the role, I paid special

attention to John-Alexander Sakelos as Peter Quince and found his performance engaging.

(I can relate to the frustrated director working with inexperienced and inept

actors.) John Floyd as Flute and Brit Herring as Snout performed their roles in

the play-within-the-play (Thisbe and Wall, respectively) with great energy.

The cast members threw themselves into this director’s adaptation

and may be admired for that, no matter how misguided his vision. What is the

point of the gender-bending switch, so that Oberon and not Titania falls in

love with Bottom? Oberon’s entrance in a strapless purple gown with a long train is

certainly startling, but the face-off between Oberon in his red gown and

Titania in her yellow (with an even longer train) becomes ludicrous.

The Folger Shakespeare Library has the largest Shakespeare

collection in the world and has always been a standard for Shakespearean

interpretation. As such, this production of the Folger’s Theatre challenges my

understanding of that historic relationship.

Comments

Post a Comment